A friend of mine has a hard time meditating in silence.

When we were having problems with the app's timer, and the bell was just ringing over and over again, she thought that was the way I had designed the timer, and preferred the sound of the ringing bell over just sitting in silence.

I told her that we were working on an update that would fix the timer so the bell didn't ring over and over, and she was disappointed. I explained that I was trying to promote meditating in silence, since listening to anything keeps the mind on the surface of consciousness. She told me she couldn't do it, that sitting in silence was too difficult and suggested I design an app for beginners.

Her comment was instructive because it reminded me of the Zen Buddhist concept of 'the beginner's mind'. As one Zen master has written, "In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert's there are few." Over the course of the last five weeks, I sought to emphasize this point with the people who came to my classes.

In the context of meditation, this means that when you sit down to meditate, you do not reflect on past experiences with meditation, since this creates a sense of expectation. If you have an amazing meditation session one day and expect to have the same kind of experience the next day, chances are pretty good that you will be disappointed and frustrated.

To get the most out of meditating in silence, you need to approach each session as though you are doing it for the very first time. Without expectation, you cannot be disappointed.

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Thursday, July 19, 2012

What is the best way to meditate?

While teaching me to be a Qigong instructor, Roger Jahnke, OMD, shared an anecdote that I have repeated many times in my classes. Even though it relates specifically to the practice of Qigong, I feel it

applies equally to the practice of meditation which, by definition, is a type of Qigong.

In the past, Roger has led trips to China to give his students a chance to immerse themselves in the history and geography of Qigong.

On one of these trips, in an encounter with a Chinese master, an American student asked:

"What is the best form of Qigong?"

The master looked puzzled by the question and then answered:

"The one you do."

As with Qigong, there are many forms of meditation borne out of myriad traditions. You can study dozens of styles, all of which are designed to bring you to the same destination, but if you don't do it on a daily basis, it doesn't matter which one you think is best.

In the past, Roger has led trips to China to give his students a chance to immerse themselves in the history and geography of Qigong.

On one of these trips, in an encounter with a Chinese master, an American student asked:

"What is the best form of Qigong?"

The master looked puzzled by the question and then answered:

"The one you do."

As with Qigong, there are many forms of meditation borne out of myriad traditions. You can study dozens of styles, all of which are designed to bring you to the same destination, but if you don't do it on a daily basis, it doesn't matter which one you think is best.

Friday, July 6, 2012

"Meditation is Bad for You!"

'Meditation is bad for you!'

Have you ever heard anyone say anything like this?

Probably not.

And you probably never will.

That's because it is easy to prove otherwise. Anyone who wants to know what meditation is, just has to do it. Both study and personal experience support the truth and power of this delicate practice. Meditation is the safest and simplest way to make you better at everything you do, and it may help you live a longer, happier life.

Then why don't we all do it?

After all, the science is in. Meditating daily physically changes the brain in a way that not only enhances health, but may be a factor in preventing illnesses associated with physical degeneration over time.

Our religious and moral codes also endorse mindfulness training - a.k.a. meditation, self-reflection, prayer - as a means to physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual improvement and fulfillment.

So why isn't it already part of everyone's everyday life?

We all know the multitude of answers to this question. All of them are excuses and none of them really matter. So instead of trying to answer this question, simply address the 'meditation deficiency' head on.

All it takes is to sit quietly with yourself for 22 minutes twice a day, just 44 minutes every 24 hours.

Consider this: It has been said that if every school-aged child in the world meditated every day, in a single generation the world would know a lasting global peace.

So what would happen if every child, teen and adult began meditating every day, beginning today?

Begin today and find out.

Have you ever heard anyone say anything like this?

Probably not.

And you probably never will.

That's because it is easy to prove otherwise. Anyone who wants to know what meditation is, just has to do it. Both study and personal experience support the truth and power of this delicate practice. Meditation is the safest and simplest way to make you better at everything you do, and it may help you live a longer, happier life.

Then why don't we all do it?

After all, the science is in. Meditating daily physically changes the brain in a way that not only enhances health, but may be a factor in preventing illnesses associated with physical degeneration over time.

Our religious and moral codes also endorse mindfulness training - a.k.a. meditation, self-reflection, prayer - as a means to physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual improvement and fulfillment.

So why isn't it already part of everyone's everyday life?

We all know the multitude of answers to this question. All of them are excuses and none of them really matter. So instead of trying to answer this question, simply address the 'meditation deficiency' head on.

All it takes is to sit quietly with yourself for 22 minutes twice a day, just 44 minutes every 24 hours.

Consider this: It has been said that if every school-aged child in the world meditated every day, in a single generation the world would know a lasting global peace.

So what would happen if every child, teen and adult began meditating every day, beginning today?

Begin today and find out.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

Sitting in Silence

My original intent was to create an app that insisted people mantra meditate for 20 minutes at a time, and in silence.

In an effort to gain wider appeal, Chutika and I agreed to make the timer adjustable, but relaxing music and guided meditation keep the mind on the surface of awareness, which is inconsistent with the experience I am promoting.

I had originally tried to keep the instructional text in the app to a minimum, but what I settled on wasn't enough. People didn't really understand the app's point of view.

So for the last few days I have been condensing the instructions from my blog, emphasizing the value of 20 minute sessions and meditating in silence. I have also asked Chutika to set the timer at 20 minutes.

Not long after I learned Transcendental Meditation, I realized how TM is different than the method of Zen meditation I learned in the 1990s. Both are done in silence, but the practice of zazen involves focusing on the breath with eyes open. This makes it more difficult to achieve the transcendent brainwave states of higher consciousness. A friend once explained that Zen meditation is a tool for living in this world. The transcendent states are not unattainable, but they are harder to achieve consistently.

In contrast, when I do TM, I focus on a 'meaningless' word with my eyes closed. Without something to anchor me in this world, it is easier to transcend time and space in just 20 minutes. It is recommended by TM teachers that one should never meditate more than twice a day, unlike Zen monks who sit for hours at a time.

Using either method, meditating for 5 or 10 minutes at a time just isn't very useful. The brain needs time to 'power down' to the more powerful brainwave states, and 20 minutes seems to be a magic number. As Deepak Chopra says, 'After twenty minutes, something wonderful happens.'

Most studies on the effects of meditation are done on subjects who meditate for 15 to 30 minutes at a time. The subjects generally show measurable physical and functional changes in the brain if they practice daily, and regularly achieving transcendent brainwave states is the key factor in those changes.

If you think sitting in absolute silence for 20 minutes is a waste of time, and doing it twice a day is twice the waste, give me a chance to convince you otherwise.

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

The Science of Meditation

The other day one of my students sent me an article from the CBC's website about a scientific study which suggested that meditating for as little as 11 hours in a month could prevent mental illness. The US-based study noted physically measurable changes in the brains of people with mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder, when they practiced a specific type of meditation.

This information may be news to some people but accounts of the benefits of meditation can be found among the oldest surviving records of human history. Daoism in China, and the teachings of Vedanta and Buddhism in India, all have hallowed traditions of 'sitting still and doing nothing' to benefit the body, mind and soul, going back thousands of years.

If you do a search of the words 'science' and 'meditation' on Wikipedia you will find an entry titled 'Research on meditation', detailing the modern history of this field starting with the work of Dr Herbert Benson. I rely heavily on Dr Benson's work to give credibility to what I do, since the word 'Qigong' carries little weight with most Canadians until they have tried it.

The CBC article came to me the day after I sent an email off to our local recreation department announcing my fall meditation classes. In the past I have always done my classes on Monday or Tuesday evenings, but since many people say those days don't work for them, I thought I'd try a different approach. Starting Monday, September 17th, I will be offering a meditation class one day a week for five weeks, on each successive day of the week, finishing on Friday, October 19th.

These classes are also different in that they are stand-alone classes rather than a series. Over the past six months, since I first started preparing for the presentation I did at LDSS, I have been refining the way I teach meditation. My hope is that a single class will give students all the information and experience they need to make meditation a daily habit. The slide show I am using for the class will be emailed to students afterwards so they can review it if they need to.

Most of the information I am sharing in these classes is already available on this blog, and I have added another page called 'Download and Print' to make it easier to access.

The goal of this blog from the beginning has been to demonstrate how simple the principles involved in meditation are, but if you're like me, you will find great benefit from attending a class. After all, there is no substitute for being in the same room as the teacher.

The cost of the class is $10 and you can contact the Rec Dept at 519-292-2054 after September 1st to register.

This information may be news to some people but accounts of the benefits of meditation can be found among the oldest surviving records of human history. Daoism in China, and the teachings of Vedanta and Buddhism in India, all have hallowed traditions of 'sitting still and doing nothing' to benefit the body, mind and soul, going back thousands of years.

If you do a search of the words 'science' and 'meditation' on Wikipedia you will find an entry titled 'Research on meditation', detailing the modern history of this field starting with the work of Dr Herbert Benson. I rely heavily on Dr Benson's work to give credibility to what I do, since the word 'Qigong' carries little weight with most Canadians until they have tried it.

The CBC article came to me the day after I sent an email off to our local recreation department announcing my fall meditation classes. In the past I have always done my classes on Monday or Tuesday evenings, but since many people say those days don't work for them, I thought I'd try a different approach. Starting Monday, September 17th, I will be offering a meditation class one day a week for five weeks, on each successive day of the week, finishing on Friday, October 19th.

These classes are also different in that they are stand-alone classes rather than a series. Over the past six months, since I first started preparing for the presentation I did at LDSS, I have been refining the way I teach meditation. My hope is that a single class will give students all the information and experience they need to make meditation a daily habit. The slide show I am using for the class will be emailed to students afterwards so they can review it if they need to.

Most of the information I am sharing in these classes is already available on this blog, and I have added another page called 'Download and Print' to make it easier to access.

The goal of this blog from the beginning has been to demonstrate how simple the principles involved in meditation are, but if you're like me, you will find great benefit from attending a class. After all, there is no substitute for being in the same room as the teacher.

The cost of the class is $10 and you can contact the Rec Dept at 519-292-2054 after September 1st to register.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Letters to the Editor

Yesterday my writing time was spent on a letter to the editor of our local newspaper. I hastily wrote a few paragraphs which I felt captured my feelings, and sent if off before my morning meditation

I should have known better.

I have a history of writing inflammatory and poorly conceived letters to editors, a pattern which began in university. In the pages of Trent University's The Arthur, more than once I made myself the centre of attention by writing what was really on my mind, revealling more about how my mind works than anything else.

The first time was after hearing the song 'Bomb the Boats and Feed the Fish' by The Forgotten Rebels over the sound system of The Ceilidh one afternoon. The reactionary side of me took deep offense to the way the woman at the next table was amused by the lyrics. Understanding that the song was referencing racist remarks made against Vietnamese refugees, I foolishly decided it was inappropriate for an institute of higher learning.

The next day I wrote to The Arthur calling for a ban on playing the song campus pubs. It was met by a chorus of equally angry letters from people who were actually around when the song was popular in 1979 and better understood its political context. The Rebels, as I discovered through these responses, were not siding with racists but using racists' words against them in sympathy with the refugees. It took a while for me to live it down. I remember being introduced to people a few times after the incident and seeing the recognition of my name dawn on their faces.

The next time I wrote to The Arthur I tried to be more careful, but I hadn't counted on a particularly vindictive editor with blurry editorial ethics. Like the removal of the keystone from a stone archway, the editor's deft excision of one sentence destroyed any remaining credibility my name might have had with the student body. In addition to editing my words to her advantage, she had also seen fit to publish a full-page attack on my letter on the opposite page. For the next two weeks, the letters' section of the paper was filled with a barrage of rebuttals to my emasculated argument.

Fortunately for me, some people had come to understand the editor was abusing her role at the paper to further her own political views, all the while ironically decrying the privileged male voice of the media. One student came to my defense with his own letter and was similarly pilloried alongside of me. Although I was outraged and even felt sorry for her new victim, I was relieved that she had shifted her attention away from me.

The main lesson I learned from these incidents was the art giving myself a cooling-off period to reflect on what I've written before sharing. Not only does it give me a chance to edit my ire, but It also helps me to more fully express my ideas so my words cannot be so easily edited to hurt me. This lesson has come to serve me well both with personal letters and those intended for public consumption.

So when I sat down yesterday morning, I really should have known better than to write something out of anger and send it off without the benefit of at least meditating beforehand. Over morning coffee I shared what I had written with Tara who readily chastised me for my poorly considered words.

So I went back to my computer and looked at what I'd written, seeing as though for the first time where my worst tendencies were represented all too well.

I did a quick and much more thoughtful edit of the letter and sent it off, hoping the editor would choose to print the revision rather than the original. Upon receiving a positive response from the editor, I reflected on how a writer is only as good as their editor, especially in the case of self-editing.

I should have known better.

I have a history of writing inflammatory and poorly conceived letters to editors, a pattern which began in university. In the pages of Trent University's The Arthur, more than once I made myself the centre of attention by writing what was really on my mind, revealling more about how my mind works than anything else.

The first time was after hearing the song 'Bomb the Boats and Feed the Fish' by The Forgotten Rebels over the sound system of The Ceilidh one afternoon. The reactionary side of me took deep offense to the way the woman at the next table was amused by the lyrics. Understanding that the song was referencing racist remarks made against Vietnamese refugees, I foolishly decided it was inappropriate for an institute of higher learning.

The next day I wrote to The Arthur calling for a ban on playing the song campus pubs. It was met by a chorus of equally angry letters from people who were actually around when the song was popular in 1979 and better understood its political context. The Rebels, as I discovered through these responses, were not siding with racists but using racists' words against them in sympathy with the refugees. It took a while for me to live it down. I remember being introduced to people a few times after the incident and seeing the recognition of my name dawn on their faces.

The next time I wrote to The Arthur I tried to be more careful, but I hadn't counted on a particularly vindictive editor with blurry editorial ethics. Like the removal of the keystone from a stone archway, the editor's deft excision of one sentence destroyed any remaining credibility my name might have had with the student body. In addition to editing my words to her advantage, she had also seen fit to publish a full-page attack on my letter on the opposite page. For the next two weeks, the letters' section of the paper was filled with a barrage of rebuttals to my emasculated argument.

Fortunately for me, some people had come to understand the editor was abusing her role at the paper to further her own political views, all the while ironically decrying the privileged male voice of the media. One student came to my defense with his own letter and was similarly pilloried alongside of me. Although I was outraged and even felt sorry for her new victim, I was relieved that she had shifted her attention away from me.

The main lesson I learned from these incidents was the art giving myself a cooling-off period to reflect on what I've written before sharing. Not only does it give me a chance to edit my ire, but It also helps me to more fully express my ideas so my words cannot be so easily edited to hurt me. This lesson has come to serve me well both with personal letters and those intended for public consumption.

So when I sat down yesterday morning, I really should have known better than to write something out of anger and send it off without the benefit of at least meditating beforehand. Over morning coffee I shared what I had written with Tara who readily chastised me for my poorly considered words.

So I went back to my computer and looked at what I'd written, seeing as though for the first time where my worst tendencies were represented all too well.

I did a quick and much more thoughtful edit of the letter and sent it off, hoping the editor would choose to print the revision rather than the original. Upon receiving a positive response from the editor, I reflected on how a writer is only as good as their editor, especially in the case of self-editing.

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Knee-Deep in the River of Zen

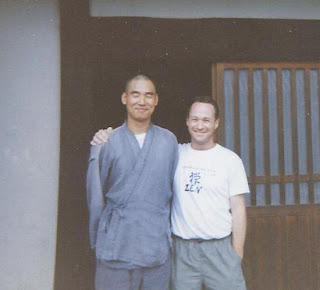

My visit to the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zendo in 1993 resulted in a brief friendship with an American exchange student named Brian.

Upon completing his undergraduate degree in history, Brian submitted a thesis proposal to study the role of feudalism in contemporary Japanese martial arts. His proposal was accepted and a year later he managed to get a Japanese university to foot the bill for a six-month stay in Kyoto.

His weekly routine in Japan's cultural capital involved classes given in English at the university, Japanese language classes, and daily workouts at the oldest jujistu dojo in the city. Wanting to round out his Japan experience even more, he managed to find the money and time to take a few days to visit the zendo after hearing about it from one of the members of the dojo.

He had never been out of the US before and every day he spent in Japan was a revelation. I enjoyed spending time with him for this reason alone. I had been in the country for two years by that time and his questions and comments on life at the zendo helped me see certain things I took for granted with fresh eyes. His enthusiasm for life at the zendo also impressed Seigo-san. As with me, Seigo took extra time to tutor Brian on any aspect of zendo life he expressed interest in.

Brian had studied Thai kickboxing in his home state of Tennessee for seven years before switching to the Japanese art of jujitsu. His knees just couldn't take the demands of the former, and the damage he had done to them frequently impeded his progress in the latter.

As Leonard Cohen once said in an interview: 'Zen is great for the mind, but hard on the knees.' Life at the zendo amplified the pain in Brian's knees in more ways than one. In addition to the demands of sitting cross-legged during zazen, sitting seiza for breakfast and dinner probably contributed more to his increased discomfort.

During the week Brian visited the zendo, a German literature professor named Peter who taught at a university in Tokyo, came to stay with another German colleague. Peter was fluent in German, English and Japanese, and his effortless ability to sit in full-lotus position for zazen impressed everyone including Seigo.

On Brian's last day at the zendo, he asked Peter for a favour. He had some very specific questions for Seigo, but since his command of Japanese wasn't the greatest and Seigo's command of English was even more rudimentary, he hoped Peter could translate for them. Peter was more than happy to oblige.

Several of the guests joined the three of them in the lounge that afternoon to share in the exchange. I remember there being a fairly harmonious group of people visiting that week, and all of us looked forward to hearing what Seigo had to say. Brian set up a camcorder on a borrowed tripod to capture the exchange for future reference and asked me to operate it.

He began with broad questions about the benefits of zazen. Seigo's face took on a serious, almost sombre expression as he answered the questions through Peter. He spoke of how daily meditation would benefit Brian's studies, his martial arts practice, and his personal relationships. He also spoke of the determination and discipline it would require, but promised the rewards would be immediate, measurable and long-lasting if he persisted with this practice.

With a competent translator for the exchange, Seigo explained in great detail the importance of posture in enhancing proper breathing during meditation, and the benefits of doing it on an empty stomach. As to the literal meanings of the words uttered during the morning sutras, he told Brian not to concern himself with them. Their primary purpose was to 'wake up' the lungs and body before morning zazen.

Finally Brian asked the question I believe weighed most on his mind: Would the pain in his knees during zazen diminish or at least get easier to bear?

Seigo became even more serious, almost dramatic as he spoke of the pain getting worse and worse. With one hand he wordlessly drew a rising arc in the air, curving up and up, suddenly dropping it in an apparent indication of when the pain would stop completely.

Brian moved to the edge of his chair and asked Seigo to clarify when this would happen. Peter translated.

For the first time during the exchange Seigo smiled a deep, full-faced smile. He looked directly at Brian and responded in English:

'When you die!'

Upon completing his undergraduate degree in history, Brian submitted a thesis proposal to study the role of feudalism in contemporary Japanese martial arts. His proposal was accepted and a year later he managed to get a Japanese university to foot the bill for a six-month stay in Kyoto.

His weekly routine in Japan's cultural capital involved classes given in English at the university, Japanese language classes, and daily workouts at the oldest jujistu dojo in the city. Wanting to round out his Japan experience even more, he managed to find the money and time to take a few days to visit the zendo after hearing about it from one of the members of the dojo.

He had never been out of the US before and every day he spent in Japan was a revelation. I enjoyed spending time with him for this reason alone. I had been in the country for two years by that time and his questions and comments on life at the zendo helped me see certain things I took for granted with fresh eyes. His enthusiasm for life at the zendo also impressed Seigo-san. As with me, Seigo took extra time to tutor Brian on any aspect of zendo life he expressed interest in.

Brian had studied Thai kickboxing in his home state of Tennessee for seven years before switching to the Japanese art of jujitsu. His knees just couldn't take the demands of the former, and the damage he had done to them frequently impeded his progress in the latter.

As Leonard Cohen once said in an interview: 'Zen is great for the mind, but hard on the knees.' Life at the zendo amplified the pain in Brian's knees in more ways than one. In addition to the demands of sitting cross-legged during zazen, sitting seiza for breakfast and dinner probably contributed more to his increased discomfort.

During the week Brian visited the zendo, a German literature professor named Peter who taught at a university in Tokyo, came to stay with another German colleague. Peter was fluent in German, English and Japanese, and his effortless ability to sit in full-lotus position for zazen impressed everyone including Seigo.

On Brian's last day at the zendo, he asked Peter for a favour. He had some very specific questions for Seigo, but since his command of Japanese wasn't the greatest and Seigo's command of English was even more rudimentary, he hoped Peter could translate for them. Peter was more than happy to oblige.

Several of the guests joined the three of them in the lounge that afternoon to share in the exchange. I remember there being a fairly harmonious group of people visiting that week, and all of us looked forward to hearing what Seigo had to say. Brian set up a camcorder on a borrowed tripod to capture the exchange for future reference and asked me to operate it.

He began with broad questions about the benefits of zazen. Seigo's face took on a serious, almost sombre expression as he answered the questions through Peter. He spoke of how daily meditation would benefit Brian's studies, his martial arts practice, and his personal relationships. He also spoke of the determination and discipline it would require, but promised the rewards would be immediate, measurable and long-lasting if he persisted with this practice.

With a competent translator for the exchange, Seigo explained in great detail the importance of posture in enhancing proper breathing during meditation, and the benefits of doing it on an empty stomach. As to the literal meanings of the words uttered during the morning sutras, he told Brian not to concern himself with them. Their primary purpose was to 'wake up' the lungs and body before morning zazen.

Finally Brian asked the question I believe weighed most on his mind: Would the pain in his knees during zazen diminish or at least get easier to bear?

Seigo became even more serious, almost dramatic as he spoke of the pain getting worse and worse. With one hand he wordlessly drew a rising arc in the air, curving up and up, suddenly dropping it in an apparent indication of when the pain would stop completely.

Brian moved to the edge of his chair and asked Seigo to clarify when this would happen. Peter translated.

For the first time during the exchange Seigo smiled a deep, full-faced smile. He looked directly at Brian and responded in English:

'When you die!'

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

Extraordinary Brainwave States

More than once I have heard a wonderful anecdote about Thomas Edison's approach to problem solving. It involved a unique method of accessing the creativity of his subconscious mind.

More than once I have heard a wonderful anecdote about Thomas Edison's approach to problem solving. It involved a unique method of accessing the creativity of his subconscious mind.As I heard it, Edison would sit in a chair with two tin pie plates on the floor, one on either side of him. Then he would hold a handful of ball bearings in each hand, close his eyes, and allow himself to nod off, all the while thinking about the particular problem he was looking to solve.

Eventually he would begin to fall asleep. As he did so, his body would begin to relax and his brain would shift into what he called 'the twilight state', that place between waking and deep sleep. When his body was relaxed enough, his hands would no longer be able to hold on to the ball bearings and they would fall onto the pie plates. The crashing sound of metal on metal would jerk him awake and, hopefully, he would awaken with a new idea on how to proceed with whatever project he was working on.

History is full of examples where revelations, discoveries, inventions, and innovations were arrived at through the act of meditation or other meditative activities:

During 40 days of fasting, meditating, and praying, Jesus resisted all sorts of evil temptations, attained his oneness with God and found his way to divine grace.

Richard Branson claims his best work is done lying in a hammock on Necker Island and staring off into space.

Mikao Usui received the secrets to Reiki while meditating.

Even though he states that one shouldn't approach meditation as the means to solve a specific problem, David Lynch says his use of Transcendental Meditation has increased his intuitive capacity.

Toshiharu Fukai credits insights he received from meditation as critical to his development of Sosei Water.

Gautama Buddha is said to have achieved Enlightenment after 49 days of meditation, and through this experience discovered The Four Noble Truths, the central tenets of Buddhism.

Dr Herbert Benson, in his book The Breakout Principle gives examples of activities - everything from doing needlework to taking a shower - which allow people to solve problems or remove blockages to creativity.

Sunday, June 3, 2012

Sound for Meditation

In 2001, about a month before we moved back to Ontario from Nelson, BC, Tara and I went to the Langham Cultural Centre in Kaslo to see/hear Pandit Shivnath Mishra and his son Deobrat perform.

In 2001, about a month before we moved back to Ontario from Nelson, BC, Tara and I went to the Langham Cultural Centre in Kaslo to see/hear Pandit Shivnath Mishra and his son Deobrat perform.There were about 20-30 people in the audience, and the father-and-son sitar duo were accompanied by a tabla player. The best thing about the performance was how the elder Mishra defied my expectations, playing in a way that one could only compare to Jimi Hendrix. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, he rocked back and forth in a frenzy as each piece progressed in tempo and volume, slamming his sitar downwards to strike either the stage or his own legs, introducing another percussive element to the ragas.

Deobrat was quite the opposite. Except for his hands, he barely moved and frequently closed his eyes as he played, his angelic face transfixing the audience as much as his father's antics did. (The album cover above captures exactly the essence of what I recall of that evening.)

It was the middle of a very hot summer and the theatre did not have air conditioning, so I had a really hard time keeping my eyes open. Despite this, it was an unforgettable experience. I never fully nodded off, and probably absorbed more of the music while in that wonderful state of consciousness between wakefulness and sleep than if I had kept my eyes open.

After the performance, the audience was invited onto the stage to ask questions about the music and the instruments. In the theatre's lobby we purchased one of the CDs they had on offer, and since then I have purchased a few more of their discs through CD Baby including a recording of Deobrat without his father, Sound for Meditation. Unlike the others, which build to an intensity Tara finds incompatible with the atmosphere of her clinic, Sound for Meditation is gentle and even-tempoed, and could be used in a yoga or Qigong class.

A few years ago, while I was working on my screen adaptation of Autobiography of a Yogi, I became friends with Deobrat on Facebook. One day I wrote to him about my screenplay and asked if he was interested in doing the music for the film. After all, the Mishras hail from Varanasi (Benares) a city which plays a significant role in Paramahansa Yogananda's story. To my delight he expressed enthusiasm for the project, telling me of his admiration for Yogananda.

It has been a few years since that exchange, so if I ever manage to get the film made, I hope he remembers his promise.

The Mishras can be seen/heard on YouTube.

Friday, June 1, 2012

Fall Classes

The other day I made the decision to do a series of one-time meditation classes in September and October. In the past I have always offered them on Monday or Tuesday night, but many people have told me those nights don't work for them, so they've never signed up. This time I am doing five separate classes over five weeks, the first on Monday, the second on Tuesday and so on. Hopefully this will give everyone interested a chance to attend.

The other day I made the decision to do a series of one-time meditation classes in September and October. In the past I have always offered them on Monday or Tuesday night, but many people have told me those nights don't work for them, so they've never signed up. This time I am doing five separate classes over five weeks, the first on Monday, the second on Tuesday and so on. Hopefully this will give everyone interested a chance to attend.The classes will be at Trinity United Church here in Listowel, where I've been teaching Qigong for the past seven years. The Parlour there is such an excellent venue with its wall-to-wall carpet, subdued lighting, comfortable chairs and sofas.

Another reason I like teaching there are the people. The minister, Reverend Steven Cox, and the office administrator, Norma MacDonald, always welcome me as an old friend whenever I drop by. Steven has a background in Asian martial arts, so he is very supportive of what I do, and Norma is just one of the nicest people you will ever meet. Even though I am not a member of the church, nor ever attended service there, the two of them make me feel as though I belong, making the church a perfect home for my classes.

Yesterday when I went to work out the dates for my classes with Norma, I had my usual brief but profound exchange with Steven, bringing him up to date with my life and my plans for the fall classes. I have never attended church with any sort of regularity, but Steven's energy and outlook have me thinking it's time I did. Maybe, one of these days...

Norma was her usual cheery self, and when I started telling her about teaching meditation at the high school, she told me she had heard all about it from her son. He was in the class for my first visit last fall, and had apparently come home impressed and inspired by my presentation.

It was tremendously gratifying to hear her words, to know that my hard work is having the desired impact on the community. It is rare that I get that kind of feedback and it inspires me to continue in this direction. Even though it is months away, I find myself looking forward to the fall when I will have a chance to introduce another group of students to the art and science of meditation.

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

The Big Stick

Before my first visit to the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zendo, the friend who was taking me there warned me about the keisaku.

In a Zen monastery of the Rinzai sect, the jikijitsu wields this long, flat stick during zazen, using it to wake up the monks who slouch or doze off. Since it was not a real monastery, getting hit with it at the Zen centre was considered optional but recommended.

I don't remember if I exercised that option on my first visit, but two years later I did. In fact, I actually came to appreciate and even look forward to being hit with it.

On that second visit, the Zen centre was being managed by a young Korean monk named Seigo. Seigo-san was extremely robust, quick to smile, and eager to see that the centre's guests got the most out of their visit. Even though the keisaku was supposed to be optional, he insisted on making it mandatory, much to the dismay of some of the guests. Given that it was offered during each half hour of meditation, this meant being hit with it twice during morning meditation and three times in the evening.

The way it worked was this: halfway through each half hour, the jikijitsu got up from his place at the front of the zendo, picked up the keisaku, and began to walk down one side of the room and back up the other. As he approached each person sitting in cross-legged meditation posture, they brought their hands together in gassho, and bowed to the monk who did the same. The person then leaned forward and steadied themself as the monk delivered three quick blows on each side of the back. They bowed to eachother again, and the monk moved on to the next person.

I liked Seigo-san as soon as I met him, but I wasn't too sure about the keisaku. It looked and sounded painful, and as he made his way towards me I started to get very nervous. What have I gotten myself into? I thought, thinking of the two-week visit ahead of me.

Nevertheless, as Seigo-san approached me I brought my hands up without hesitation. I bowed and leaned foward, steadying myself on the edge of the raised platform that ran along each side of the room. I'm sure my heart was racing as he probed my back with his hand. After a moment I heard the stick cut through the air and felt it hit my back three times on each side of the spine, striking the muscles between the spine and the shoulder blades.

What surprised me was not just how little and briefly it hurt, but how much better my back felt afterwards. In fact, the sensation wasn't really what I would call painful since the contact was so brief and the stick so flexible. The technique, developed over a thousand years ago, was perfect for instantly releasing whatever tension had built up in my back during meditation. As I type these words, I am aware of a similar tension from working on my computer and wish Seigo was here to hit me again!

The keisaku, as I now understand, is not the form of punishment it appears to be but a form of therapy. In relating this story to others I have likened it to getting a rapid massage. The brief probing Seigo-san did of my back prior to delivering the blows was exploratory, so he knew exactly where the tension was and where to strike effectively.

During my subsequent visits to the Zen centre over the next four years, I received the keisaku from a number of different people, but none was as competent and exact as Seigo-san.

In the very short time we knew eachother we developed a close friendship. I gave him English lessons in the evening, and in return he gave me chiropractic adjustments and detailed instruction in the morning's Qigong routine.

Towards the end of my two-week stay, one of the other guests remarked on how obvious the monk's affection for me was to everyone. 'He hits you harder than anyone else,' he said. 'He must really like you.'

In a Zen monastery of the Rinzai sect, the jikijitsu wields this long, flat stick during zazen, using it to wake up the monks who slouch or doze off. Since it was not a real monastery, getting hit with it at the Zen centre was considered optional but recommended.

I don't remember if I exercised that option on my first visit, but two years later I did. In fact, I actually came to appreciate and even look forward to being hit with it.

On that second visit, the Zen centre was being managed by a young Korean monk named Seigo. Seigo-san was extremely robust, quick to smile, and eager to see that the centre's guests got the most out of their visit. Even though the keisaku was supposed to be optional, he insisted on making it mandatory, much to the dismay of some of the guests. Given that it was offered during each half hour of meditation, this meant being hit with it twice during morning meditation and three times in the evening.

The way it worked was this: halfway through each half hour, the jikijitsu got up from his place at the front of the zendo, picked up the keisaku, and began to walk down one side of the room and back up the other. As he approached each person sitting in cross-legged meditation posture, they brought their hands together in gassho, and bowed to the monk who did the same. The person then leaned forward and steadied themself as the monk delivered three quick blows on each side of the back. They bowed to eachother again, and the monk moved on to the next person.

I liked Seigo-san as soon as I met him, but I wasn't too sure about the keisaku. It looked and sounded painful, and as he made his way towards me I started to get very nervous. What have I gotten myself into? I thought, thinking of the two-week visit ahead of me.

Nevertheless, as Seigo-san approached me I brought my hands up without hesitation. I bowed and leaned foward, steadying myself on the edge of the raised platform that ran along each side of the room. I'm sure my heart was racing as he probed my back with his hand. After a moment I heard the stick cut through the air and felt it hit my back three times on each side of the spine, striking the muscles between the spine and the shoulder blades.

What surprised me was not just how little and briefly it hurt, but how much better my back felt afterwards. In fact, the sensation wasn't really what I would call painful since the contact was so brief and the stick so flexible. The technique, developed over a thousand years ago, was perfect for instantly releasing whatever tension had built up in my back during meditation. As I type these words, I am aware of a similar tension from working on my computer and wish Seigo was here to hit me again!

The keisaku, as I now understand, is not the form of punishment it appears to be but a form of therapy. In relating this story to others I have likened it to getting a rapid massage. The brief probing Seigo-san did of my back prior to delivering the blows was exploratory, so he knew exactly where the tension was and where to strike effectively.

During my subsequent visits to the Zen centre over the next four years, I received the keisaku from a number of different people, but none was as competent and exact as Seigo-san.

In the very short time we knew eachother we developed a close friendship. I gave him English lessons in the evening, and in return he gave me chiropractic adjustments and detailed instruction in the morning's Qigong routine.

Towards the end of my two-week stay, one of the other guests remarked on how obvious the monk's affection for me was to everyone. 'He hits you harder than anyone else,' he said. 'He must really like you.'

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Heart Focus

One of the techniques I share with my students comes from the research of The Institute of HeartMath.

In my last posting I spoke of the connection between the brain, the heart and the gut. HeartMath specializes in understanding and exploiting the connection between the brain and the heart to improve mental health.

Their research speaks of the value of balancing the activity of the brain with that of the heart, a phenomenon known as 'coherence'. Low coherence is the state when people are least likely to make good decisions under duress, and high coherence - or 'The Zone' - is the place where an individual is in a better position to perform well in spite of stressful conditions.

The result of frequent coherence training is resilience to stress. After all, you can't eliminate stress, but you can strengthen your ability to handle it through increased resilience.

HeartMath has developed a line of biofeedback products designed to teach people how to achieve and maintain high coherence states by measuring and displaying heart rate variability. Many of their products are designed to help kids do better in school by teaching them what high coherence feels like, and include games and graphic displays.

I purchased one of HeartMath's PC-based biofeedback units - the emWave - and have found it is useful for showing people how simple it is to achieve high coherence. However, as much as I respect and value their work, you don't need to purchase anything from them to do this. All you need to do is close your eyes, place one hand on your chest in the area of the heart and focus on positive thoughts.

Last year, while I was using the emWave with a client during a stress management training session, I witnessed first-hand how quickly one can move into high coherence. I hooked him up to the emWave, and the graph immediately showed him to be in low coherence. When he put his hand on his heart, he immediately achieved a high coherence reading and was able to maintain that state through positive focus.

So, if none of the more conventional meditation/mindfulness methods appeal to you, all you have to do is close your eyes, put your hand on your heart and think about whatever makes you feel good. Start with 5 minutes at a time, once or twice a day and increase it to 20 at your own pace.

In my last posting I spoke of the connection between the brain, the heart and the gut. HeartMath specializes in understanding and exploiting the connection between the brain and the heart to improve mental health.

Their research speaks of the value of balancing the activity of the brain with that of the heart, a phenomenon known as 'coherence'. Low coherence is the state when people are least likely to make good decisions under duress, and high coherence - or 'The Zone' - is the place where an individual is in a better position to perform well in spite of stressful conditions.

The result of frequent coherence training is resilience to stress. After all, you can't eliminate stress, but you can strengthen your ability to handle it through increased resilience.

HeartMath has developed a line of biofeedback products designed to teach people how to achieve and maintain high coherence states by measuring and displaying heart rate variability. Many of their products are designed to help kids do better in school by teaching them what high coherence feels like, and include games and graphic displays.

I purchased one of HeartMath's PC-based biofeedback units - the emWave - and have found it is useful for showing people how simple it is to achieve high coherence. However, as much as I respect and value their work, you don't need to purchase anything from them to do this. All you need to do is close your eyes, place one hand on your chest in the area of the heart and focus on positive thoughts.

Last year, while I was using the emWave with a client during a stress management training session, I witnessed first-hand how quickly one can move into high coherence. I hooked him up to the emWave, and the graph immediately showed him to be in low coherence. When he put his hand on his heart, he immediately achieved a high coherence reading and was able to maintain that state through positive focus.

So, if none of the more conventional meditation/mindfulness methods appeal to you, all you have to do is close your eyes, put your hand on your heart and think about whatever makes you feel good. Start with 5 minutes at a time, once or twice a day and increase it to 20 at your own pace.

Friday, May 25, 2012

Head, Heart and Gut

While at the Zen centre during Golden Week in the mid-90s, I suffered from a persistent pain in my gut. I could barely sit to meditate, and the herbal remedy someone suggested I take for it had no effect. I didn't have a fever and, as far as I could tell, there was no clear reason for my discomfort.

One afternoon, I had a long and tense conversation with my Japanese girlfriend, who was at school in England, via the payphone in the zendo's common room. Lisa, an Australian woman I knew from Nagoya was also in the room and had heard part of our conversation. After I got off the phone, she apologized for eavesdropping but politely asked about the call.

I explained how my original plan for the August holiday was to visit Canada, in particular to spend as much time at the family cottage as possible. My girlfriend was taking advantage of her proximity to mainland Europe, travelling around the continent as much as she could before her year of studying abroad came to an end. She wanted to go to Finland, Norway and Sweden in August and, after much debating back and forth, I had reluctantly agreed to meet her there.

I also spoke to Lisa at great length of what a beautiful a place the cottage was. There must have something significant in the way I was speaking that gave her a clue to my inner turmoil. During a pause in my words, she said 'Boy, you really want to visit Canada in August.' Until that point I hadn't recognized how strong my emotions around my changed plans were. I had accepted on one level that my girlfriend wanted to me to come to Europe and talked myself into it.

At Lisa's words I realized in a flash how badly I wanted to come to Canada. I promptly called my girlfriend back, announcing to her that I wasn't going to meet her in Europe, was going to the cottage instead, and expressed my hope that she would come, too. We had a bit of a charged exchange after that, but after I got off the phone the first thing I noticed was how the pain in my gut, which had been with me night and day for the previous week, was gone.

It wasn't until many years later that I was able to truly understand what had been going on with my gut at the time. Fairly recently I learned the heart is comprised of neurons as well as muscle tissue, and that there are neural ganglia which connect the brain with the heart and the stomach. The most interesting aspect of this is how this connection confirms the TCM model of the body's three energy centres known as dantian.

My decision to acede to my girlfriend's wishes was a decision made in my head. I was attempting to please her at the expense of what was going on in my heart. That's when the gut kicked in, attempting to pull my focus down to my heart, to get me to acknowledge my true feelings. And it wasn't until Lisa gave me her feedback that I understood how much I was trying to go against what I wanted 'in my heart'.

For much of human history, our language has expressed the relationship between head, heart and gut through such expressions as 'follow your heart' and 'gut feeling'. The ancient wisdom of India, China and Greece expressed this, placing the mind - the centre of volition - in the heart. But this model for understanding the body was superceded in the West by one which gave primacy to the brain and the intellect.

It is only recently that advances in neuroscience, which have given rise to the disciplines of neurocardiology and neurogastroenterology, that doctors are understanding that the original model wasn't just poetic expression: we are primarily feeling beings; feelings are centred in the heart, not the brain; and the gut plays a significant role in this relationship.

The lesson here is clear: if we think too much about something at the expense of what we feel we will make wrong decisions about everything, from what we choose as a career to who we end up with as a life partner.

The brain is important, but it is in our hearts that we know the real truth about who we are and what we should do, moment to moment.

This is why meditation is so useful. It helps us balance where we place our cognitive emphasis, to pay appropriate attention to what our head, heart and gut are telling us at any given time, and help us to make better decisions about everything.

One afternoon, I had a long and tense conversation with my Japanese girlfriend, who was at school in England, via the payphone in the zendo's common room. Lisa, an Australian woman I knew from Nagoya was also in the room and had heard part of our conversation. After I got off the phone, she apologized for eavesdropping but politely asked about the call.

I explained how my original plan for the August holiday was to visit Canada, in particular to spend as much time at the family cottage as possible. My girlfriend was taking advantage of her proximity to mainland Europe, travelling around the continent as much as she could before her year of studying abroad came to an end. She wanted to go to Finland, Norway and Sweden in August and, after much debating back and forth, I had reluctantly agreed to meet her there.

I also spoke to Lisa at great length of what a beautiful a place the cottage was. There must have something significant in the way I was speaking that gave her a clue to my inner turmoil. During a pause in my words, she said 'Boy, you really want to visit Canada in August.' Until that point I hadn't recognized how strong my emotions around my changed plans were. I had accepted on one level that my girlfriend wanted to me to come to Europe and talked myself into it.

At Lisa's words I realized in a flash how badly I wanted to come to Canada. I promptly called my girlfriend back, announcing to her that I wasn't going to meet her in Europe, was going to the cottage instead, and expressed my hope that she would come, too. We had a bit of a charged exchange after that, but after I got off the phone the first thing I noticed was how the pain in my gut, which had been with me night and day for the previous week, was gone.

It wasn't until many years later that I was able to truly understand what had been going on with my gut at the time. Fairly recently I learned the heart is comprised of neurons as well as muscle tissue, and that there are neural ganglia which connect the brain with the heart and the stomach. The most interesting aspect of this is how this connection confirms the TCM model of the body's three energy centres known as dantian.

My decision to acede to my girlfriend's wishes was a decision made in my head. I was attempting to please her at the expense of what was going on in my heart. That's when the gut kicked in, attempting to pull my focus down to my heart, to get me to acknowledge my true feelings. And it wasn't until Lisa gave me her feedback that I understood how much I was trying to go against what I wanted 'in my heart'.

For much of human history, our language has expressed the relationship between head, heart and gut through such expressions as 'follow your heart' and 'gut feeling'. The ancient wisdom of India, China and Greece expressed this, placing the mind - the centre of volition - in the heart. But this model for understanding the body was superceded in the West by one which gave primacy to the brain and the intellect.

It is only recently that advances in neuroscience, which have given rise to the disciplines of neurocardiology and neurogastroenterology, that doctors are understanding that the original model wasn't just poetic expression: we are primarily feeling beings; feelings are centred in the heart, not the brain; and the gut plays a significant role in this relationship.

The lesson here is clear: if we think too much about something at the expense of what we feel we will make wrong decisions about everything, from what we choose as a career to who we end up with as a life partner.

The brain is important, but it is in our hearts that we know the real truth about who we are and what we should do, moment to moment.

This is why meditation is so useful. It helps us balance where we place our cognitive emphasis, to pay appropriate attention to what our head, heart and gut are telling us at any given time, and help us to make better decisions about everything.

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Social Innovation

A few years ago while on vacation, I noticed something about the airports I was travelling through: they were noisy.

Sitting in the crowded waiting area with a good hour ahead of me that day, without a phone or computer to distract me, I was keenly aware of the level and variety of noise around me. People were talking on their phones, saying nothing as far as I could tell, adding to the din of a television no one was watching over my head, the roar of aircraft outside, the announcements inside: a melting pot of noise.

I changed seats, hoping to find somewhere quieter, but it was as though the noise level in the airport was a constant, a given, something that was simply part of the overall experience. It seemed to add hours to my wait and take years off my life.

Since then, I can't travel without taking note of the level of noise people are being subjected to in airports. I have terrible ears, scarred from primitive medical interventions, and in places with high levels of ambient noise, I am easily irritated. That's why I now travel with foam earplugs in my pocket.

In Pearson (the airport that serves Toronto) as with most airports in North America today, every waiting area has its own flat screen TV, broadcasting nothing but bad and/or useless news. The irony is that, in this day and age, most people in airports and elsewhere are plugged into their Pods & Berries, making the TVs superfluous.

The last time I was in Pearson, the only one paying attention to the TV seemed to be me, and it wasn't the content that caught my eyes and ears: I was wishing I had a remote control with a mute button, like the one I rely upon heavily at home to spare me the blare of commercials. It was something of an awakening for me.

I thought about writing to the GTAA to tell them that they could save a lot of money by removing the TVs, selling them, and cancelling their cable bill. In my not-so-humble opinion, it would be the first step they could take to change the airport's status as worst airport in Canada, an honour it truly deserves.

But the awakening I speak of did not result in an indignant letter to the GTAA, but gave birth instead to an idea: airports designed as refuges from the noise of travelling in an airplane. At the very least I thought airport designers should consider creating media-free zones where people had no wi-fi or cell coverage, where they could give themselves a break FROM ALL THAT NOISE!

It also led me to coin the phrase 'meditate while-u-wait'. I imagined not just airports, but hospital waiting rooms, subway cars...anyplace where people were sitting and waiting: to arrive, to see someone, to give or receive bad news...

I put together a concept poster, showing a man sitting in a chair, accompanied by instructions on how to meditate in a public space. Fantasizing about getting the campaign adopted by the TTC, I emailed my concepts to a non-profit in Toronto called the Centre for Social Innovation - or CSI - and after several weeks heard nothing from them. I called them twice and left messages - one voicemail and one with the person who answered the phone at their Spadina office - but again, no one got back to me. It was like the David Lynch Foundation all over again, as though no one wanted to hear my ideas.

So I created a website just to spread the message of 'Meditate While-U-Wait' with my friends via email and FB, and asked a few of them to translate the instructions into French, Spanish, and Farsi for me. Still, I got the sense that my ideas were disappearing into a black hole.

Now I have abandoned all my other online efforts to be a writer and teacher in favour of developing the phone app. The blogs and websites I once had such hopes for are no longer accessible to the public, though I visit them from time to time, cannabilizing ideas and text to integrate on this blog in hope that this focus will help my ideas catch on.

The irony is that I am developing an iPhone app, but I don't have an iPhone, nor a Smartphone, not even a cell.

I'm just looking for an effective strategy to spread these ideas.

Sitting in the crowded waiting area with a good hour ahead of me that day, without a phone or computer to distract me, I was keenly aware of the level and variety of noise around me. People were talking on their phones, saying nothing as far as I could tell, adding to the din of a television no one was watching over my head, the roar of aircraft outside, the announcements inside: a melting pot of noise.

I changed seats, hoping to find somewhere quieter, but it was as though the noise level in the airport was a constant, a given, something that was simply part of the overall experience. It seemed to add hours to my wait and take years off my life.

Since then, I can't travel without taking note of the level of noise people are being subjected to in airports. I have terrible ears, scarred from primitive medical interventions, and in places with high levels of ambient noise, I am easily irritated. That's why I now travel with foam earplugs in my pocket.

In Pearson (the airport that serves Toronto) as with most airports in North America today, every waiting area has its own flat screen TV, broadcasting nothing but bad and/or useless news. The irony is that, in this day and age, most people in airports and elsewhere are plugged into their Pods & Berries, making the TVs superfluous.

The last time I was in Pearson, the only one paying attention to the TV seemed to be me, and it wasn't the content that caught my eyes and ears: I was wishing I had a remote control with a mute button, like the one I rely upon heavily at home to spare me the blare of commercials. It was something of an awakening for me.

I thought about writing to the GTAA to tell them that they could save a lot of money by removing the TVs, selling them, and cancelling their cable bill. In my not-so-humble opinion, it would be the first step they could take to change the airport's status as worst airport in Canada, an honour it truly deserves.

But the awakening I speak of did not result in an indignant letter to the GTAA, but gave birth instead to an idea: airports designed as refuges from the noise of travelling in an airplane. At the very least I thought airport designers should consider creating media-free zones where people had no wi-fi or cell coverage, where they could give themselves a break FROM ALL THAT NOISE!

It also led me to coin the phrase 'meditate while-u-wait'. I imagined not just airports, but hospital waiting rooms, subway cars...anyplace where people were sitting and waiting: to arrive, to see someone, to give or receive bad news...

I put together a concept poster, showing a man sitting in a chair, accompanied by instructions on how to meditate in a public space. Fantasizing about getting the campaign adopted by the TTC, I emailed my concepts to a non-profit in Toronto called the Centre for Social Innovation - or CSI - and after several weeks heard nothing from them. I called them twice and left messages - one voicemail and one with the person who answered the phone at their Spadina office - but again, no one got back to me. It was like the David Lynch Foundation all over again, as though no one wanted to hear my ideas.

So I created a website just to spread the message of 'Meditate While-U-Wait' with my friends via email and FB, and asked a few of them to translate the instructions into French, Spanish, and Farsi for me. Still, I got the sense that my ideas were disappearing into a black hole.

Now I have abandoned all my other online efforts to be a writer and teacher in favour of developing the phone app. The blogs and websites I once had such hopes for are no longer accessible to the public, though I visit them from time to time, cannabilizing ideas and text to integrate on this blog in hope that this focus will help my ideas catch on.

The irony is that I am developing an iPhone app, but I don't have an iPhone, nor a Smartphone, not even a cell.

I'm just looking for an effective strategy to spread these ideas.

Monday, May 21, 2012

Meditation in the Classroom

American filmmaker David Lynch has been doing Transcendental Meditation twice a day, every day, since 1973. In 2005, he formed a foundation to teach TM to schoolchildren and people considered to be 'at risk'.

A few years ago I received an email with a quote from Lynch's book about TM, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. I bought a copy, read it, and promptly sent an email to The David Lynch Foundation asking how I could become involved in bringing TM to my local schools.

I soon received an email from someone who is part of the DLF's "Canadian operations". He followed the email up with a phone call but I wasn't home for the call. In his message he said he would try calling later, but I never heard from him again. He didn't leave a phone number for me to reach him at, and neither he nor DLF ever responded to my subsequent emails.

In the meantime, I watched a number of You Tube videos about DLF. Seeing an auditorium filled with school kids doing TM convinced me that I should be teaching kids to meditate.

So I contacted the local school board to find out if they wanted me to instruct teachers on how to make meditation part of their school routine. I suggested it could be part of a professional development day, but the stumbling block seemed to be an unwillingness to pay for such a service. I was told I would probably have to get the teachers to agree to bear the cost, and how unlikely it was that they would be willing to shell out as little as $10-20 per person.

Next I wrote to various ministers in the Ontario government urging them to mandate meditation in the classroom. Someone from the education minister's office informed me that the province's revised school curricula suggests meditation for Grades 1-8 to address substance abuse, and for Grades 11 and 12 to manage stress.

Somewhere along the way I wrote an email to the principal's office of the local high school suggesting they hire me to teach meditation to their teachers, but I never received any kind of reply.

I also learned TM and introduced mantra meditation to my classes.

Eventually I got a break when two teachers from the high school approached me to teach meditation to their Grade 12 Philosophy class. They asked if I could discuss meditation in the context of Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian philosophical traditions. So I put together a Powerpoint presentation covering the bare essentials of the Dao, the Buddha, and Confucius, finishing up with a 20-minute meditation.

For the most part the kids were receptive to the whole experience, and the feedback I got from the teachers was very positive. My visit was even covered by the local paper.

In fact, it was that experience that led me here.

In my effort to create a useful, impactful presentation for those schoolkids, I convinced myself that I had simplified the art and science of meditation to the point that anyone could learn it, with or without a teacher, using just this blog and the soon-to-be-released iPhone/iPad app.

Only time will tell if I'm right.

A few years ago I received an email with a quote from Lynch's book about TM, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. I bought a copy, read it, and promptly sent an email to The David Lynch Foundation asking how I could become involved in bringing TM to my local schools.

I soon received an email from someone who is part of the DLF's "Canadian operations". He followed the email up with a phone call but I wasn't home for the call. In his message he said he would try calling later, but I never heard from him again. He didn't leave a phone number for me to reach him at, and neither he nor DLF ever responded to my subsequent emails.

In the meantime, I watched a number of You Tube videos about DLF. Seeing an auditorium filled with school kids doing TM convinced me that I should be teaching kids to meditate.

So I contacted the local school board to find out if they wanted me to instruct teachers on how to make meditation part of their school routine. I suggested it could be part of a professional development day, but the stumbling block seemed to be an unwillingness to pay for such a service. I was told I would probably have to get the teachers to agree to bear the cost, and how unlikely it was that they would be willing to shell out as little as $10-20 per person.

Next I wrote to various ministers in the Ontario government urging them to mandate meditation in the classroom. Someone from the education minister's office informed me that the province's revised school curricula suggests meditation for Grades 1-8 to address substance abuse, and for Grades 11 and 12 to manage stress.

Somewhere along the way I wrote an email to the principal's office of the local high school suggesting they hire me to teach meditation to their teachers, but I never received any kind of reply.

I also learned TM and introduced mantra meditation to my classes.

Eventually I got a break when two teachers from the high school approached me to teach meditation to their Grade 12 Philosophy class. They asked if I could discuss meditation in the context of Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian philosophical traditions. So I put together a Powerpoint presentation covering the bare essentials of the Dao, the Buddha, and Confucius, finishing up with a 20-minute meditation.

For the most part the kids were receptive to the whole experience, and the feedback I got from the teachers was very positive. My visit was even covered by the local paper.

In fact, it was that experience that led me here.

In my effort to create a useful, impactful presentation for those schoolkids, I convinced myself that I had simplified the art and science of meditation to the point that anyone could learn it, with or without a teacher, using just this blog and the soon-to-be-released iPhone/iPad app.

Only time will tell if I'm right.

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Filling the Mind

A couple of years ago, in the months before his death, my uncle asked me why meditating was so difficult. He had struggled with mental health for most of his life, and had tried unsuccessfully to make meditation part of his daily routine more than once.

Many people are under the impression that learning to meditate means that you sit down, close your eyes and empty your mind. Those that try meditating with this expectation decide pretty quickly that it is too difficult and give up.

I think this is what my uncle experienced. So, if he were here today, I'd tell him to stop trying to empty his mind.

Over the past eight years, I have taught different types of meditation in my classes, but I now teach mantra meditation based on how I was taught Transcendental Meditation. Giving the 'mind monkey' something to do in the form of a mantra allows us to, as David Lynch says in Catching the Big Fish, 'dive deep into the ocean of consciousness'.

There are all kinds of products available to people seeking the peace of mind promised by meditation. They can choose to relax with CDs or MP3s of New Age music, the sounds of waves or forests, or guided meditation. These can be useful tools for teaching the value of stillness but, in my experience, they keep you on the surface of consciousness.

This is not to say that by practicing mantra meditation one can expect to have profound, deep experiences every time they sit. Each meditation session is different for me. Sometimes time drags; other times - like this morning - it flies by. Sometimes I feel amazing, rested and brimming with insights afterwards; other times I feel frustrated, agitated and tired.

The hardest part about meditating is deciding to do it. Understanding that I shouldn't expect the same experience each time I meditate makes it easier to do it every day. Each time I decide to sit in that kind of silence, I gain something, even if it isn't obvious at the time.

Many people are under the impression that learning to meditate means that you sit down, close your eyes and empty your mind. Those that try meditating with this expectation decide pretty quickly that it is too difficult and give up.

I think this is what my uncle experienced. So, if he were here today, I'd tell him to stop trying to empty his mind.

Over the past eight years, I have taught different types of meditation in my classes, but I now teach mantra meditation based on how I was taught Transcendental Meditation. Giving the 'mind monkey' something to do in the form of a mantra allows us to, as David Lynch says in Catching the Big Fish, 'dive deep into the ocean of consciousness'.

There are all kinds of products available to people seeking the peace of mind promised by meditation. They can choose to relax with CDs or MP3s of New Age music, the sounds of waves or forests, or guided meditation. These can be useful tools for teaching the value of stillness but, in my experience, they keep you on the surface of consciousness.

This is not to say that by practicing mantra meditation one can expect to have profound, deep experiences every time they sit. Each meditation session is different for me. Sometimes time drags; other times - like this morning - it flies by. Sometimes I feel amazing, rested and brimming with insights afterwards; other times I feel frustrated, agitated and tired.

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Noises

A few minutes into this morning's meditation, out of all of the sounds going on in the room, the sound of our kitchen clock suddenly came into focus, competing with my mantra for my attention.

Worse than the noises of traffic, or the intermittent hum of the refrigerator, a ticking clock can easy hijack your attention, and along with it, the rhythms of your mantra and your breathing. I seem to remember my TM teacher telling me to avoid meditating in a room with a clock.

I got up, crossed the room and removed the clock from the wall, putting it on a pillow which readily absorbed its pronounced ticking. On the way back to my 'meditation chair' I slid open the glass door to our deck to bring in the bird noises from outside. They always provide a nice backdrop for meditation.

As I settled back into my meditation, the bird sounds reminded me of my first time at the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zen Center. In summer, the cicadas would sing all day, their sound pouring through the open, unscreened windows. They are so loud in Japan that when I first arrived I thought the noise they were making was from a local species of bird.

During evening meditation in the zendo, the song of the cicadas filled the room, but as I counted my breaths, I ceased to notice that they were even there.

Until they stopped.

Not long after the sun went down, the cicadas abruptly stopped their singing, all of them, all at once. The first time it happened was like being hit with the keisaku, causing me to re-adjust my posture and restart my counting.

During meditation the next evening, my focus drifted from my counting and fixed on the singing cicadas. Completely distracted by them, as the sun set, I anticipated the moment when they would go silent again.

Worse than the noises of traffic, or the intermittent hum of the refrigerator, a ticking clock can easy hijack your attention, and along with it, the rhythms of your mantra and your breathing. I seem to remember my TM teacher telling me to avoid meditating in a room with a clock.

I got up, crossed the room and removed the clock from the wall, putting it on a pillow which readily absorbed its pronounced ticking. On the way back to my 'meditation chair' I slid open the glass door to our deck to bring in the bird noises from outside. They always provide a nice backdrop for meditation.

As I settled back into my meditation, the bird sounds reminded me of my first time at the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zen Center. In summer, the cicadas would sing all day, their sound pouring through the open, unscreened windows. They are so loud in Japan that when I first arrived I thought the noise they were making was from a local species of bird.

During evening meditation in the zendo, the song of the cicadas filled the room, but as I counted my breaths, I ceased to notice that they were even there.

Until they stopped.