Before my first visit to the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zendo, the friend who was taking me there warned me about the keisaku.

In a Zen monastery of the Rinzai sect, the jikijitsu wields this long, flat stick during zazen, using it to wake up the monks who slouch or doze off. Since it was not a real monastery, getting hit with it at the Zen centre was considered optional but recommended.

I don't remember if I exercised that option on my first visit, but two years later I did. In fact, I actually came to appreciate and even look forward to being hit with it.

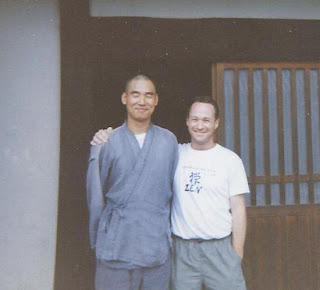

On that second visit, the Zen centre was being managed by a young Korean monk named Seigo. Seigo-san was extremely robust, quick to smile, and eager to see that the centre's guests got the most out of their visit. Even though the keisaku was supposed to be optional, he insisted on making it mandatory, much to the dismay of some of the guests. Given that it was offered during each half hour of meditation, this meant being hit with it twice during morning meditation and three times in the evening.

The way it worked was this: halfway through each half hour, the jikijitsu got up from his place at the front of the zendo, picked up the keisaku, and began to walk down one side of the room and back up the other. As he approached each person sitting in cross-legged meditation posture, they brought their hands together in gassho, and bowed to the monk who did the same. The person then leaned forward and steadied themself as the monk delivered three quick blows on each side of the back. They bowed to eachother again, and the monk moved on to the next person.

I liked Seigo-san as soon as I met him, but I wasn't too sure about the keisaku. It looked and sounded painful, and as he made his way towards me I started to get very nervous. What have I gotten myself into? I thought, thinking of the two-week visit ahead of me.

Nevertheless, as Seigo-san approached me I brought my hands up without hesitation. I bowed and leaned foward, steadying myself on the edge of the raised platform that ran along each side of the room. I'm sure my heart was racing as he probed my back with his hand. After a moment I heard the stick cut through the air and felt it hit my back three times on each side of the spine, striking the muscles between the spine and the shoulder blades.

What surprised me was not just how little and briefly it hurt, but how much better my back felt afterwards. In fact, the sensation wasn't really what I would call painful since the contact was so brief and the stick so flexible. The technique, developed over a thousand years ago, was perfect for instantly releasing whatever tension had built up in my back during meditation. As I type these words, I am aware of a similar tension from working on my computer and wish Seigo was here to hit me again!

The keisaku, as I now understand, is not the form of punishment it appears to be but a form of therapy. In relating this story to others I have likened it to getting a rapid massage. The brief probing Seigo-san did of my back prior to delivering the blows was exploratory, so he knew exactly where the tension was and where to strike effectively.

During my subsequent visits to the Zen centre over the next four years, I received the keisaku from a number of different people, but none was as competent and exact as Seigo-san.

In the very short time we knew eachother we developed a close friendship. I gave him English lessons in the evening, and in return he gave me chiropractic adjustments and detailed instruction in the morning's Qigong routine.

Towards the end of my two-week stay, one of the other guests remarked on how obvious the monk's affection for me was to everyone. 'He hits you harder than anyone else,' he said. 'He must really like you.'

No comments:

Post a Comment