Before my first visit to the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zendo, the friend who was taking me there warned me about the keisaku.

In a Zen monastery of the Rinzai sect, the jikijitsu wields this long, flat stick during zazen, using it to wake up the monks who slouch or doze off. Since it was not a real monastery, getting hit with it at the Zen centre was considered optional but recommended.

I don't remember if I exercised that option on my first visit, but two years later I did. In fact, I actually came to appreciate and even look forward to being hit with it.

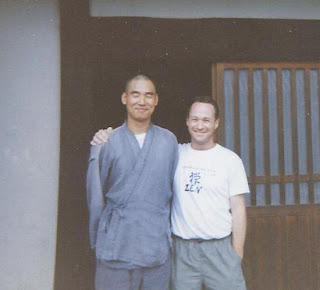

On that second visit, the Zen centre was being managed by a young Korean monk named Seigo. Seigo-san was extremely robust, quick to smile, and eager to see that the centre's guests got the most out of their visit. Even though the keisaku was supposed to be optional, he insisted on making it mandatory, much to the dismay of some of the guests. Given that it was offered during each half hour of meditation, this meant being hit with it twice during morning meditation and three times in the evening.

The way it worked was this: halfway through each half hour, the jikijitsu got up from his place at the front of the zendo, picked up the keisaku, and began to walk down one side of the room and back up the other. As he approached each person sitting in cross-legged meditation posture, they brought their hands together in gassho, and bowed to the monk who did the same. The person then leaned forward and steadied themself as the monk delivered three quick blows on each side of the back. They bowed to eachother again, and the monk moved on to the next person.

I liked Seigo-san as soon as I met him, but I wasn't too sure about the keisaku. It looked and sounded painful, and as he made his way towards me I started to get very nervous. What have I gotten myself into? I thought, thinking of the two-week visit ahead of me.

Nevertheless, as Seigo-san approached me I brought my hands up without hesitation. I bowed and leaned foward, steadying myself on the edge of the raised platform that ran along each side of the room. I'm sure my heart was racing as he probed my back with his hand. After a moment I heard the stick cut through the air and felt it hit my back three times on each side of the spine, striking the muscles between the spine and the shoulder blades.

What surprised me was not just how little and briefly it hurt, but how much better my back felt afterwards. In fact, the sensation wasn't really what I would call painful since the contact was so brief and the stick so flexible. The technique, developed over a thousand years ago, was perfect for instantly releasing whatever tension had built up in my back during meditation. As I type these words, I am aware of a similar tension from working on my computer and wish Seigo was here to hit me again!

The keisaku, as I now understand, is not the form of punishment it appears to be but a form of therapy. In relating this story to others I have likened it to getting a rapid massage. The brief probing Seigo-san did of my back prior to delivering the blows was exploratory, so he knew exactly where the tension was and where to strike effectively.

During my subsequent visits to the Zen centre over the next four years, I received the keisaku from a number of different people, but none was as competent and exact as Seigo-san.

In the very short time we knew eachother we developed a close friendship. I gave him English lessons in the evening, and in return he gave me chiropractic adjustments and detailed instruction in the morning's Qigong routine.

Towards the end of my two-week stay, one of the other guests remarked on how obvious the monk's affection for me was to everyone. 'He hits you harder than anyone else,' he said. 'He must really like you.'

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

Saturday, May 26, 2012

Heart Focus

One of the techniques I share with my students comes from the research of The Institute of HeartMath.

In my last posting I spoke of the connection between the brain, the heart and the gut. HeartMath specializes in understanding and exploiting the connection between the brain and the heart to improve mental health.

Their research speaks of the value of balancing the activity of the brain with that of the heart, a phenomenon known as 'coherence'. Low coherence is the state when people are least likely to make good decisions under duress, and high coherence - or 'The Zone' - is the place where an individual is in a better position to perform well in spite of stressful conditions.

The result of frequent coherence training is resilience to stress. After all, you can't eliminate stress, but you can strengthen your ability to handle it through increased resilience.

HeartMath has developed a line of biofeedback products designed to teach people how to achieve and maintain high coherence states by measuring and displaying heart rate variability. Many of their products are designed to help kids do better in school by teaching them what high coherence feels like, and include games and graphic displays.

I purchased one of HeartMath's PC-based biofeedback units - the emWave - and have found it is useful for showing people how simple it is to achieve high coherence. However, as much as I respect and value their work, you don't need to purchase anything from them to do this. All you need to do is close your eyes, place one hand on your chest in the area of the heart and focus on positive thoughts.

Last year, while I was using the emWave with a client during a stress management training session, I witnessed first-hand how quickly one can move into high coherence. I hooked him up to the emWave, and the graph immediately showed him to be in low coherence. When he put his hand on his heart, he immediately achieved a high coherence reading and was able to maintain that state through positive focus.

So, if none of the more conventional meditation/mindfulness methods appeal to you, all you have to do is close your eyes, put your hand on your heart and think about whatever makes you feel good. Start with 5 minutes at a time, once or twice a day and increase it to 20 at your own pace.

In my last posting I spoke of the connection between the brain, the heart and the gut. HeartMath specializes in understanding and exploiting the connection between the brain and the heart to improve mental health.

Their research speaks of the value of balancing the activity of the brain with that of the heart, a phenomenon known as 'coherence'. Low coherence is the state when people are least likely to make good decisions under duress, and high coherence - or 'The Zone' - is the place where an individual is in a better position to perform well in spite of stressful conditions.

The result of frequent coherence training is resilience to stress. After all, you can't eliminate stress, but you can strengthen your ability to handle it through increased resilience.

HeartMath has developed a line of biofeedback products designed to teach people how to achieve and maintain high coherence states by measuring and displaying heart rate variability. Many of their products are designed to help kids do better in school by teaching them what high coherence feels like, and include games and graphic displays.

I purchased one of HeartMath's PC-based biofeedback units - the emWave - and have found it is useful for showing people how simple it is to achieve high coherence. However, as much as I respect and value their work, you don't need to purchase anything from them to do this. All you need to do is close your eyes, place one hand on your chest in the area of the heart and focus on positive thoughts.

Last year, while I was using the emWave with a client during a stress management training session, I witnessed first-hand how quickly one can move into high coherence. I hooked him up to the emWave, and the graph immediately showed him to be in low coherence. When he put his hand on his heart, he immediately achieved a high coherence reading and was able to maintain that state through positive focus.

So, if none of the more conventional meditation/mindfulness methods appeal to you, all you have to do is close your eyes, put your hand on your heart and think about whatever makes you feel good. Start with 5 minutes at a time, once or twice a day and increase it to 20 at your own pace.

Friday, May 25, 2012

Head, Heart and Gut

While at the Zen centre during Golden Week in the mid-90s, I suffered from a persistent pain in my gut. I could barely sit to meditate, and the herbal remedy someone suggested I take for it had no effect. I didn't have a fever and, as far as I could tell, there was no clear reason for my discomfort.

One afternoon, I had a long and tense conversation with my Japanese girlfriend, who was at school in England, via the payphone in the zendo's common room. Lisa, an Australian woman I knew from Nagoya was also in the room and had heard part of our conversation. After I got off the phone, she apologized for eavesdropping but politely asked about the call.

I explained how my original plan for the August holiday was to visit Canada, in particular to spend as much time at the family cottage as possible. My girlfriend was taking advantage of her proximity to mainland Europe, travelling around the continent as much as she could before her year of studying abroad came to an end. She wanted to go to Finland, Norway and Sweden in August and, after much debating back and forth, I had reluctantly agreed to meet her there.

I also spoke to Lisa at great length of what a beautiful a place the cottage was. There must have something significant in the way I was speaking that gave her a clue to my inner turmoil. During a pause in my words, she said 'Boy, you really want to visit Canada in August.' Until that point I hadn't recognized how strong my emotions around my changed plans were. I had accepted on one level that my girlfriend wanted to me to come to Europe and talked myself into it.

At Lisa's words I realized in a flash how badly I wanted to come to Canada. I promptly called my girlfriend back, announcing to her that I wasn't going to meet her in Europe, was going to the cottage instead, and expressed my hope that she would come, too. We had a bit of a charged exchange after that, but after I got off the phone the first thing I noticed was how the pain in my gut, which had been with me night and day for the previous week, was gone.

It wasn't until many years later that I was able to truly understand what had been going on with my gut at the time. Fairly recently I learned the heart is comprised of neurons as well as muscle tissue, and that there are neural ganglia which connect the brain with the heart and the stomach. The most interesting aspect of this is how this connection confirms the TCM model of the body's three energy centres known as dantian.

My decision to acede to my girlfriend's wishes was a decision made in my head. I was attempting to please her at the expense of what was going on in my heart. That's when the gut kicked in, attempting to pull my focus down to my heart, to get me to acknowledge my true feelings. And it wasn't until Lisa gave me her feedback that I understood how much I was trying to go against what I wanted 'in my heart'.

For much of human history, our language has expressed the relationship between head, heart and gut through such expressions as 'follow your heart' and 'gut feeling'. The ancient wisdom of India, China and Greece expressed this, placing the mind - the centre of volition - in the heart. But this model for understanding the body was superceded in the West by one which gave primacy to the brain and the intellect.

It is only recently that advances in neuroscience, which have given rise to the disciplines of neurocardiology and neurogastroenterology, that doctors are understanding that the original model wasn't just poetic expression: we are primarily feeling beings; feelings are centred in the heart, not the brain; and the gut plays a significant role in this relationship.

The lesson here is clear: if we think too much about something at the expense of what we feel we will make wrong decisions about everything, from what we choose as a career to who we end up with as a life partner.

The brain is important, but it is in our hearts that we know the real truth about who we are and what we should do, moment to moment.

This is why meditation is so useful. It helps us balance where we place our cognitive emphasis, to pay appropriate attention to what our head, heart and gut are telling us at any given time, and help us to make better decisions about everything.

One afternoon, I had a long and tense conversation with my Japanese girlfriend, who was at school in England, via the payphone in the zendo's common room. Lisa, an Australian woman I knew from Nagoya was also in the room and had heard part of our conversation. After I got off the phone, she apologized for eavesdropping but politely asked about the call.

I explained how my original plan for the August holiday was to visit Canada, in particular to spend as much time at the family cottage as possible. My girlfriend was taking advantage of her proximity to mainland Europe, travelling around the continent as much as she could before her year of studying abroad came to an end. She wanted to go to Finland, Norway and Sweden in August and, after much debating back and forth, I had reluctantly agreed to meet her there.

I also spoke to Lisa at great length of what a beautiful a place the cottage was. There must have something significant in the way I was speaking that gave her a clue to my inner turmoil. During a pause in my words, she said 'Boy, you really want to visit Canada in August.' Until that point I hadn't recognized how strong my emotions around my changed plans were. I had accepted on one level that my girlfriend wanted to me to come to Europe and talked myself into it.

At Lisa's words I realized in a flash how badly I wanted to come to Canada. I promptly called my girlfriend back, announcing to her that I wasn't going to meet her in Europe, was going to the cottage instead, and expressed my hope that she would come, too. We had a bit of a charged exchange after that, but after I got off the phone the first thing I noticed was how the pain in my gut, which had been with me night and day for the previous week, was gone.

It wasn't until many years later that I was able to truly understand what had been going on with my gut at the time. Fairly recently I learned the heart is comprised of neurons as well as muscle tissue, and that there are neural ganglia which connect the brain with the heart and the stomach. The most interesting aspect of this is how this connection confirms the TCM model of the body's three energy centres known as dantian.

My decision to acede to my girlfriend's wishes was a decision made in my head. I was attempting to please her at the expense of what was going on in my heart. That's when the gut kicked in, attempting to pull my focus down to my heart, to get me to acknowledge my true feelings. And it wasn't until Lisa gave me her feedback that I understood how much I was trying to go against what I wanted 'in my heart'.

For much of human history, our language has expressed the relationship between head, heart and gut through such expressions as 'follow your heart' and 'gut feeling'. The ancient wisdom of India, China and Greece expressed this, placing the mind - the centre of volition - in the heart. But this model for understanding the body was superceded in the West by one which gave primacy to the brain and the intellect.

It is only recently that advances in neuroscience, which have given rise to the disciplines of neurocardiology and neurogastroenterology, that doctors are understanding that the original model wasn't just poetic expression: we are primarily feeling beings; feelings are centred in the heart, not the brain; and the gut plays a significant role in this relationship.

The lesson here is clear: if we think too much about something at the expense of what we feel we will make wrong decisions about everything, from what we choose as a career to who we end up with as a life partner.

The brain is important, but it is in our hearts that we know the real truth about who we are and what we should do, moment to moment.

This is why meditation is so useful. It helps us balance where we place our cognitive emphasis, to pay appropriate attention to what our head, heart and gut are telling us at any given time, and help us to make better decisions about everything.

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Social Innovation

A few years ago while on vacation, I noticed something about the airports I was travelling through: they were noisy.

Sitting in the crowded waiting area with a good hour ahead of me that day, without a phone or computer to distract me, I was keenly aware of the level and variety of noise around me. People were talking on their phones, saying nothing as far as I could tell, adding to the din of a television no one was watching over my head, the roar of aircraft outside, the announcements inside: a melting pot of noise.

I changed seats, hoping to find somewhere quieter, but it was as though the noise level in the airport was a constant, a given, something that was simply part of the overall experience. It seemed to add hours to my wait and take years off my life.

Since then, I can't travel without taking note of the level of noise people are being subjected to in airports. I have terrible ears, scarred from primitive medical interventions, and in places with high levels of ambient noise, I am easily irritated. That's why I now travel with foam earplugs in my pocket.

In Pearson (the airport that serves Toronto) as with most airports in North America today, every waiting area has its own flat screen TV, broadcasting nothing but bad and/or useless news. The irony is that, in this day and age, most people in airports and elsewhere are plugged into their Pods & Berries, making the TVs superfluous.

The last time I was in Pearson, the only one paying attention to the TV seemed to be me, and it wasn't the content that caught my eyes and ears: I was wishing I had a remote control with a mute button, like the one I rely upon heavily at home to spare me the blare of commercials. It was something of an awakening for me.

I thought about writing to the GTAA to tell them that they could save a lot of money by removing the TVs, selling them, and cancelling their cable bill. In my not-so-humble opinion, it would be the first step they could take to change the airport's status as worst airport in Canada, an honour it truly deserves.

But the awakening I speak of did not result in an indignant letter to the GTAA, but gave birth instead to an idea: airports designed as refuges from the noise of travelling in an airplane. At the very least I thought airport designers should consider creating media-free zones where people had no wi-fi or cell coverage, where they could give themselves a break FROM ALL THAT NOISE!

It also led me to coin the phrase 'meditate while-u-wait'. I imagined not just airports, but hospital waiting rooms, subway cars...anyplace where people were sitting and waiting: to arrive, to see someone, to give or receive bad news...

I put together a concept poster, showing a man sitting in a chair, accompanied by instructions on how to meditate in a public space. Fantasizing about getting the campaign adopted by the TTC, I emailed my concepts to a non-profit in Toronto called the Centre for Social Innovation - or CSI - and after several weeks heard nothing from them. I called them twice and left messages - one voicemail and one with the person who answered the phone at their Spadina office - but again, no one got back to me. It was like the David Lynch Foundation all over again, as though no one wanted to hear my ideas.

So I created a website just to spread the message of 'Meditate While-U-Wait' with my friends via email and FB, and asked a few of them to translate the instructions into French, Spanish, and Farsi for me. Still, I got the sense that my ideas were disappearing into a black hole.

Now I have abandoned all my other online efforts to be a writer and teacher in favour of developing the phone app. The blogs and websites I once had such hopes for are no longer accessible to the public, though I visit them from time to time, cannabilizing ideas and text to integrate on this blog in hope that this focus will help my ideas catch on.

The irony is that I am developing an iPhone app, but I don't have an iPhone, nor a Smartphone, not even a cell.

I'm just looking for an effective strategy to spread these ideas.

Sitting in the crowded waiting area with a good hour ahead of me that day, without a phone or computer to distract me, I was keenly aware of the level and variety of noise around me. People were talking on their phones, saying nothing as far as I could tell, adding to the din of a television no one was watching over my head, the roar of aircraft outside, the announcements inside: a melting pot of noise.

I changed seats, hoping to find somewhere quieter, but it was as though the noise level in the airport was a constant, a given, something that was simply part of the overall experience. It seemed to add hours to my wait and take years off my life.

Since then, I can't travel without taking note of the level of noise people are being subjected to in airports. I have terrible ears, scarred from primitive medical interventions, and in places with high levels of ambient noise, I am easily irritated. That's why I now travel with foam earplugs in my pocket.

In Pearson (the airport that serves Toronto) as with most airports in North America today, every waiting area has its own flat screen TV, broadcasting nothing but bad and/or useless news. The irony is that, in this day and age, most people in airports and elsewhere are plugged into their Pods & Berries, making the TVs superfluous.

The last time I was in Pearson, the only one paying attention to the TV seemed to be me, and it wasn't the content that caught my eyes and ears: I was wishing I had a remote control with a mute button, like the one I rely upon heavily at home to spare me the blare of commercials. It was something of an awakening for me.

I thought about writing to the GTAA to tell them that they could save a lot of money by removing the TVs, selling them, and cancelling their cable bill. In my not-so-humble opinion, it would be the first step they could take to change the airport's status as worst airport in Canada, an honour it truly deserves.

But the awakening I speak of did not result in an indignant letter to the GTAA, but gave birth instead to an idea: airports designed as refuges from the noise of travelling in an airplane. At the very least I thought airport designers should consider creating media-free zones where people had no wi-fi or cell coverage, where they could give themselves a break FROM ALL THAT NOISE!

It also led me to coin the phrase 'meditate while-u-wait'. I imagined not just airports, but hospital waiting rooms, subway cars...anyplace where people were sitting and waiting: to arrive, to see someone, to give or receive bad news...

I put together a concept poster, showing a man sitting in a chair, accompanied by instructions on how to meditate in a public space. Fantasizing about getting the campaign adopted by the TTC, I emailed my concepts to a non-profit in Toronto called the Centre for Social Innovation - or CSI - and after several weeks heard nothing from them. I called them twice and left messages - one voicemail and one with the person who answered the phone at their Spadina office - but again, no one got back to me. It was like the David Lynch Foundation all over again, as though no one wanted to hear my ideas.

So I created a website just to spread the message of 'Meditate While-U-Wait' with my friends via email and FB, and asked a few of them to translate the instructions into French, Spanish, and Farsi for me. Still, I got the sense that my ideas were disappearing into a black hole.

Now I have abandoned all my other online efforts to be a writer and teacher in favour of developing the phone app. The blogs and websites I once had such hopes for are no longer accessible to the public, though I visit them from time to time, cannabilizing ideas and text to integrate on this blog in hope that this focus will help my ideas catch on.

The irony is that I am developing an iPhone app, but I don't have an iPhone, nor a Smartphone, not even a cell.

I'm just looking for an effective strategy to spread these ideas.

Monday, May 21, 2012

Meditation in the Classroom

American filmmaker David Lynch has been doing Transcendental Meditation twice a day, every day, since 1973. In 2005, he formed a foundation to teach TM to schoolchildren and people considered to be 'at risk'.

A few years ago I received an email with a quote from Lynch's book about TM, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. I bought a copy, read it, and promptly sent an email to The David Lynch Foundation asking how I could become involved in bringing TM to my local schools.

I soon received an email from someone who is part of the DLF's "Canadian operations". He followed the email up with a phone call but I wasn't home for the call. In his message he said he would try calling later, but I never heard from him again. He didn't leave a phone number for me to reach him at, and neither he nor DLF ever responded to my subsequent emails.

In the meantime, I watched a number of You Tube videos about DLF. Seeing an auditorium filled with school kids doing TM convinced me that I should be teaching kids to meditate.

So I contacted the local school board to find out if they wanted me to instruct teachers on how to make meditation part of their school routine. I suggested it could be part of a professional development day, but the stumbling block seemed to be an unwillingness to pay for such a service. I was told I would probably have to get the teachers to agree to bear the cost, and how unlikely it was that they would be willing to shell out as little as $10-20 per person.

Next I wrote to various ministers in the Ontario government urging them to mandate meditation in the classroom. Someone from the education minister's office informed me that the province's revised school curricula suggests meditation for Grades 1-8 to address substance abuse, and for Grades 11 and 12 to manage stress.

Somewhere along the way I wrote an email to the principal's office of the local high school suggesting they hire me to teach meditation to their teachers, but I never received any kind of reply.

I also learned TM and introduced mantra meditation to my classes.

Eventually I got a break when two teachers from the high school approached me to teach meditation to their Grade 12 Philosophy class. They asked if I could discuss meditation in the context of Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian philosophical traditions. So I put together a Powerpoint presentation covering the bare essentials of the Dao, the Buddha, and Confucius, finishing up with a 20-minute meditation.

For the most part the kids were receptive to the whole experience, and the feedback I got from the teachers was very positive. My visit was even covered by the local paper.

In fact, it was that experience that led me here.

In my effort to create a useful, impactful presentation for those schoolkids, I convinced myself that I had simplified the art and science of meditation to the point that anyone could learn it, with or without a teacher, using just this blog and the soon-to-be-released iPhone/iPad app.

Only time will tell if I'm right.

A few years ago I received an email with a quote from Lynch's book about TM, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. I bought a copy, read it, and promptly sent an email to The David Lynch Foundation asking how I could become involved in bringing TM to my local schools.

I soon received an email from someone who is part of the DLF's "Canadian operations". He followed the email up with a phone call but I wasn't home for the call. In his message he said he would try calling later, but I never heard from him again. He didn't leave a phone number for me to reach him at, and neither he nor DLF ever responded to my subsequent emails.

In the meantime, I watched a number of You Tube videos about DLF. Seeing an auditorium filled with school kids doing TM convinced me that I should be teaching kids to meditate.

So I contacted the local school board to find out if they wanted me to instruct teachers on how to make meditation part of their school routine. I suggested it could be part of a professional development day, but the stumbling block seemed to be an unwillingness to pay for such a service. I was told I would probably have to get the teachers to agree to bear the cost, and how unlikely it was that they would be willing to shell out as little as $10-20 per person.

Next I wrote to various ministers in the Ontario government urging them to mandate meditation in the classroom. Someone from the education minister's office informed me that the province's revised school curricula suggests meditation for Grades 1-8 to address substance abuse, and for Grades 11 and 12 to manage stress.

Somewhere along the way I wrote an email to the principal's office of the local high school suggesting they hire me to teach meditation to their teachers, but I never received any kind of reply.

I also learned TM and introduced mantra meditation to my classes.

Eventually I got a break when two teachers from the high school approached me to teach meditation to their Grade 12 Philosophy class. They asked if I could discuss meditation in the context of Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian philosophical traditions. So I put together a Powerpoint presentation covering the bare essentials of the Dao, the Buddha, and Confucius, finishing up with a 20-minute meditation.

For the most part the kids were receptive to the whole experience, and the feedback I got from the teachers was very positive. My visit was even covered by the local paper.

In fact, it was that experience that led me here.

In my effort to create a useful, impactful presentation for those schoolkids, I convinced myself that I had simplified the art and science of meditation to the point that anyone could learn it, with or without a teacher, using just this blog and the soon-to-be-released iPhone/iPad app.

Only time will tell if I'm right.

Sunday, May 20, 2012

Filling the Mind

A couple of years ago, in the months before his death, my uncle asked me why meditating was so difficult. He had struggled with mental health for most of his life, and had tried unsuccessfully to make meditation part of his daily routine more than once.

Many people are under the impression that learning to meditate means that you sit down, close your eyes and empty your mind. Those that try meditating with this expectation decide pretty quickly that it is too difficult and give up.

I think this is what my uncle experienced. So, if he were here today, I'd tell him to stop trying to empty his mind.

Over the past eight years, I have taught different types of meditation in my classes, but I now teach mantra meditation based on how I was taught Transcendental Meditation. Giving the 'mind monkey' something to do in the form of a mantra allows us to, as David Lynch says in Catching the Big Fish, 'dive deep into the ocean of consciousness'.

There are all kinds of products available to people seeking the peace of mind promised by meditation. They can choose to relax with CDs or MP3s of New Age music, the sounds of waves or forests, or guided meditation. These can be useful tools for teaching the value of stillness but, in my experience, they keep you on the surface of consciousness.

This is not to say that by practicing mantra meditation one can expect to have profound, deep experiences every time they sit. Each meditation session is different for me. Sometimes time drags; other times - like this morning - it flies by. Sometimes I feel amazing, rested and brimming with insights afterwards; other times I feel frustrated, agitated and tired.

The hardest part about meditating is deciding to do it. Understanding that I shouldn't expect the same experience each time I meditate makes it easier to do it every day. Each time I decide to sit in that kind of silence, I gain something, even if it isn't obvious at the time.

Many people are under the impression that learning to meditate means that you sit down, close your eyes and empty your mind. Those that try meditating with this expectation decide pretty quickly that it is too difficult and give up.

I think this is what my uncle experienced. So, if he were here today, I'd tell him to stop trying to empty his mind.

Over the past eight years, I have taught different types of meditation in my classes, but I now teach mantra meditation based on how I was taught Transcendental Meditation. Giving the 'mind monkey' something to do in the form of a mantra allows us to, as David Lynch says in Catching the Big Fish, 'dive deep into the ocean of consciousness'.

There are all kinds of products available to people seeking the peace of mind promised by meditation. They can choose to relax with CDs or MP3s of New Age music, the sounds of waves or forests, or guided meditation. These can be useful tools for teaching the value of stillness but, in my experience, they keep you on the surface of consciousness.

This is not to say that by practicing mantra meditation one can expect to have profound, deep experiences every time they sit. Each meditation session is different for me. Sometimes time drags; other times - like this morning - it flies by. Sometimes I feel amazing, rested and brimming with insights afterwards; other times I feel frustrated, agitated and tired.

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Noises

A few minutes into this morning's meditation, out of all of the sounds going on in the room, the sound of our kitchen clock suddenly came into focus, competing with my mantra for my attention.

Worse than the noises of traffic, or the intermittent hum of the refrigerator, a ticking clock can easy hijack your attention, and along with it, the rhythms of your mantra and your breathing. I seem to remember my TM teacher telling me to avoid meditating in a room with a clock.

I got up, crossed the room and removed the clock from the wall, putting it on a pillow which readily absorbed its pronounced ticking. On the way back to my 'meditation chair' I slid open the glass door to our deck to bring in the bird noises from outside. They always provide a nice backdrop for meditation.

As I settled back into my meditation, the bird sounds reminded me of my first time at the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zen Center. In summer, the cicadas would sing all day, their sound pouring through the open, unscreened windows. They are so loud in Japan that when I first arrived I thought the noise they were making was from a local species of bird.

During evening meditation in the zendo, the song of the cicadas filled the room, but as I counted my breaths, I ceased to notice that they were even there.

Until they stopped.

Not long after the sun went down, the cicadas abruptly stopped their singing, all of them, all at once. The first time it happened was like being hit with the keisaku, causing me to re-adjust my posture and restart my counting.

During meditation the next evening, my focus drifted from my counting and fixed on the singing cicadas. Completely distracted by them, as the sun set, I anticipated the moment when they would go silent again.

Worse than the noises of traffic, or the intermittent hum of the refrigerator, a ticking clock can easy hijack your attention, and along with it, the rhythms of your mantra and your breathing. I seem to remember my TM teacher telling me to avoid meditating in a room with a clock.

I got up, crossed the room and removed the clock from the wall, putting it on a pillow which readily absorbed its pronounced ticking. On the way back to my 'meditation chair' I slid open the glass door to our deck to bring in the bird noises from outside. They always provide a nice backdrop for meditation.

As I settled back into my meditation, the bird sounds reminded me of my first time at the Shinsho-ji Kokusai Zen Center. In summer, the cicadas would sing all day, their sound pouring through the open, unscreened windows. They are so loud in Japan that when I first arrived I thought the noise they were making was from a local species of bird.

During evening meditation in the zendo, the song of the cicadas filled the room, but as I counted my breaths, I ceased to notice that they were even there.

Until they stopped.

Not long after the sun went down, the cicadas abruptly stopped their singing, all of them, all at once. The first time it happened was like being hit with the keisaku, causing me to re-adjust my posture and restart my counting.

During meditation the next evening, my focus drifted from my counting and fixed on the singing cicadas. Completely distracted by them, as the sun set, I anticipated the moment when they would go silent again.

Friday, May 18, 2012

Yogi

I became quite obsessed with the book after buying the audiobook (read by Sir Ben Kingsley) for my girlfriend for Christmas a few years ago. That same year my sister gave me an iPod shuffle, which I promptly loaded up with my computer's music collection. But after a few weeks of listening to Sir Ben tell this wonderful story in the car, I erased all the music on my iPod and replaced it with all 18 discs of AoaY.

I don't usually walk around listening to an iPod. When I bought a Walkman in 1983, I found the act of walking around with headphones far too disorienting. But here I was walking around the supermarket, hearing about Mukunda's desire to run away and live among the Himalayan saints as I put discounted organic chicken breasts in a plastic bag.

Listening to the book multiple times, replaying my favourite passages over and over, triggered my cinematic aspirations as never before. I found a public domain copy of AoaY on-line, downloaded some free screenwriting software, and proceeded to pare the book down to a 100-page screenplay. After listening to the book for almost two years, it took me just a year to shape it into the story I was most interested in telling. I think it is pretty good, but have yet to hear any other opinions.

I had a lot of reasons for writing the screenplay, but I'm now most interested in making a film to popularize meditation among younger people. Yogananda's childhood in India is full of humour and wisdom. I could see this as an animated film as poignant as Kirikou and the Sorceress.

I have sent a copy of the script out into the world, but I know of at least one other person who has written similar screenplay. Given the popularity of the book, I can't imagine we are the only ones with this dream, that no one has tried to turn this book into a film before us. Perhaps there are legal issues too expensive to be worthwhile, but maybe, someday, Steven Spielberg or George Clooney will hear Ben Kinglsey read this wonderful book. Or maybe they will call me because they were given a copy of my script and they liked it.

While I'm waiting for that call, I will continue to teach meditation in community and private classes, keep a blog to teach people how to meditate in public places, and offer private classes on-line.

The instructional pages of this blog are designed to integrate with my upcoming teaching tool: a free app for iPhones and iPads. There are lots of apps with music and soundscapes to meditate to, but Taming the Mind Monkey is designed to teach users to meditate to silence. It should be available for download by next month.

I have been practicing and studying various kinds of meditation for twenty years, and teaching for almost nine. Since learning Transcendental Meditation a year ago, I have become obsessed with teaching 'institutional meditation'. Inspired by the work of The David Lynch Foundation, I want schools, businesses, professional organizations, etc. to adopt the practice of meditating twice daily, for 20 minutes each time.

I can think of no simpler way to make life better for everyone.

But you don't need the app to learn how to meditate. You don't even need an iDevice.

Everything you need to know, to learn how to meditate, is on this website, free to use and share.

Just view the pages in the order they are listed in the right hand column, starting with 'What is a Mind Monkey?'

Enjoy your life!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)